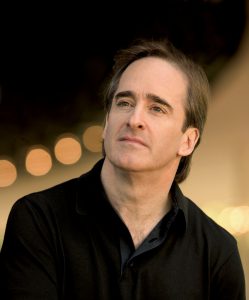

In a city that often shows scant regard for history, the Los Angeles Opera is undertaking an extraordinary project of reclamation. Under the banner “Recovered Voices,” James Conlon, in his second season as the company’s music director, is reviving operas suppressed by the Nazis.

Next Sunday Mr. Conlon, 57, is to conduct the project’s first fully staged production, a double bill of “Der Zwerg” (“The Dwarf”) by Alexander Zemlinsky and “Der Zerbrochene Krug” (“The Broken Jug”), which Viktor Ullmann composed not long before being interned in the Theresienstadt concentration camp. (He died two years later in Auschwitz.)

Though such works have been unearthed in Europe at least since the 1970s, they have yet to take root in America, where Mr. Conlon has for years extolled their virtues. But “Recovered Voices” has already raised nearly $5 million to stage some of these operas.

“You could do any number of 50 works,” Mr. Conlon said recently of the available repertory. “But I wanted to start with Zemlinsky because it was through him that I became familiar with this whole subject, which then became a mission. Besides, I consider ‘Zwerg’ one of the greatest operas of the 20th century.”

“Der Zerbrochene Krug,” here in its American premiere, is new to Mr. Conlon. But he has a long history with another Ullmann opera, “Der Kaiser von Atlantis” (“The Emperor of Atlantis”), a work for small forces that he has conducted more than half a dozen times, often in synagogues.

Works by Walter Braunfels, Ernst Krenek, Erich Wolfgang Korngold and others damaged or destroyed by Hitler’s rise and the Holocaust also figure regularly in Mr. Conlon’s programs, whether operatic, orchestral or choral. He is the music director of the Ravinia Festival near Chicago and the Cincinnati May Festival, and he has recently branched out into dance. At the Juilliard School in December he conducted a program of works newly choreographed to music by Zemlinsky, Franz Schreker and Erwin Schulhoff.

Inevitably questions of motive surround discussions of such music and its creators, who are susceptible to everything from pity to opportunism. Mr. Conlon is sensitive to such queries.

“I am not interested in tokenism or novelty,” he said. “I am not a specialty conductor, nor do I want this to be viewed as specialty repertory. This is an integral part of German music. These are not people from outer space. They have the same roots and came out of the same environment as everyone else in their time.”

Though not all music lovers may be ready to embrace a host of unfamiliar composers as heirs to Weber and Wagner and siblings to Strauss, Mr. Conlon is not alone in his view.

Michael Haas, the music curator at the Jewish Museum in Vienna, suggests a similar interpretation of 20th-century music history. Like Mr. Conlon, he speaks less as an academic than as someone with practical experience, having produced the acclaimed Entartete Musik (Degenerate Music) series for the Decca label in the 1990s, which anticipated Mr. Conlon’s work.

“Most of this music was banned because of Jewish authorship,” Mr. Haas said. “But if you look at the people who aspired to follow Wagner, you see a lot of successful Jewish composers who were building on what came before, while the non-Jewish composers, like Webern, Berg and Krenek, were far more adventurous. By banning Jewish composers, Hitler shot himself in the foot.”

Mr. Haas argues that early-to-mid-20th-century Jewish composers, many as secular as their non-Jewish counterparts, thrived in a musical landscape where tonality and Romantic impulses reigned. He also suggests that their scores represent musical bridges.

“Between Mahler and Schoenberg what is there?” Mr. Haas asked. “Well, there’s Schreker. He’s the missing link. He could not have been more central, and with his disappearance, so went an important chapter in music history.”

Yet even if advocates like Mr. Conlon reclaim that chapter, there is no guarantee that people will want to hear the music. So moving audiences and critics beyond their presuppositions becomes important.

“A lot of people think that this music is all about the Holocaust,” Mr. Conlon said, “but only 2 percent of it was written in concentration camps. This is about the restoration of two generations of composers that were wiped off the map, a tremendous variety of composers.”

To direct “Der Zwerg” and “Der Zerbrochene Krug,” Mr. Conlon has enlisted Darko Tresnjak, a Shakespeare specialist and former student of Andrei Serban who was recently appointed co-artistic director of the Old Globe theaters in San Diego. His background in the classics should prove an asset, for “Der Zwerg” is based on Oscar Wilde’s short story “The Birthday of the Infanta,” and “Der Zerbrochene Krug” on Heinrich von Kleist’s one-act comedy of that name.

“Der Zwerg” tells of an ugly but soulful dwarf, unaware of his physical appearance, who is a given to the Spanish infanta as a birthday present. Mocked by nearly all but the princess, he promptly falls in love with her, only to be rejected. When he eventually sees his reflection, he dies brokenhearted, realizing why he will never be loved.

The plot of “Der Zerbrochene Krug” has all the makings of a Preston Sturges movie, centering on a trial in which the judge himself is the guilty party. Though it ends in broad humor, the material’s serious subtext of perverted justice doubtless appealed to its victimized composer.

Mr. Conlon first approached Mr. Tresnjak about two and a half years ago, before “Recovered Voices” existed. The plan then was for a trilogy of rarely heard one-act operas by Mussorgsky, Krenek and Benjamin Fleischmann, considered by the Los Angeles Opera but now scheduled for the Juilliard School in November.

At the time Mr. Tresnjak knew no music by any of the suppressed composers dear to Mr. Conlon. But he has become a zealous convert, and the two now share a vision.

“I love it when people like James come along,” Mr. Tresnjak said. “It renews the way I look at my craft and takes me in another direction. I’m very comfortable that all of this would not be happening without James’s passion. That’s the driving force.”

Because these operas are unknown to most audiences, Mr. Conlon and Mr. Tresnjak agreed to present them straightforwardly. “There’s no point in deconstructing something the public doesn’t know,” Mr. Tresnjak said. “That doesn’t mean no interpretation. But the focus should be on clear storytelling and characterizations. That is of utmost importance.”

“Las Meninas,” Velázquez’s seminal 1656 painting depicting life at the court of King Philip IV of Spain, inspired the designs for “Der Zwerg.” For “Der Zerbrochene Krug,” which opens the program, the setting is a Dutch village square rather than the provincial courtroom called for in Kleist’s play, but the action remains in the early 19th century.

Mr. Tresnjak initially presented Mr. Conlon with three options for the Zemlinsky opera. “I said, ‘Here’s the Velázquez version, the 1920s version and the contemporary Los Angeles version,’ ” Mr. Tresnjak recalled. “I made the case for all three. Ultimately James felt most strongly about the Velázquez version, as did I, because that’s what I heard in the music. From those opening chords I saw that painting.”

But artistic vision alone does not get operas produced. Money is necessary, and lots of it. Marilyn Ziering, a philanthropist and a member of the Los Angeles Opera board with an interest in Jewish causes, made the initial gift to “Recovered Voices” in late 2006, donating $3.25 million and raising $750,000 from family and friends. Then, a year ago, the company produced a well-received preview program as prelude to the imminent double bill.

Mr. Conlon promises one production per season, with “Die Vögel” (“The Birds”) by Braunfels scheduled for next year and “Die Gezeichneten” (“The Stigmatized”) by Schreker planned for 2010.

Will the financing keep pace? For now, the company says, the “Recovered Voices” fund is at $4.85 million and growing.

“I would love to see the music of these composers played in every great opera house,” Mrs. Ziering said. “I want people to see the beauty of what was lost, and how much more beauty there could have been if we lived in a kinder world.”

Mr. Conlon, a son of left-leaning Roman Catholics, takes a more confrontational approach when it comes to giving these composers a fair hearing.

“All my life questions of social justice and injustice have been very alive in my consciousness,” he said. “This is what I think fires me up more than anything else, the anger that in the 60 or 70 years since these events occurred, the perpetrators succeeded in wiping out any trace of the art of these people. You cannot undo the injustice of the lost lives or the cruelty. But in the case of the composers you can do the one thing that would have meant the most to them, which is to perform their music.”