L.A. Opera Director Comes to Music Academy for ‘The Marriage of Figaro.’

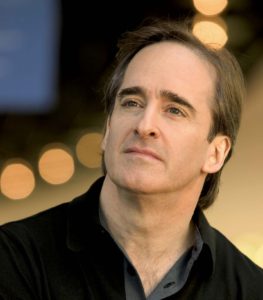

One subtle pleasure running through the work of the vocal program at the Music Academy of the West is the way that each season reflects the extraordinary impact of Marilyn Horne. In an art form defined by collaboration, mentorship, and legacy, Horne stands apart as an exceptional maven, one from whom there are few degrees of separation in any important musical direction. That’s why it’s surprising that maestro James Conlon is only now making his debut at the Music Academy of the West, and also why it’s not surprising that Conlon and “Jackie,” as he refers to Horne, are already longtime friends. As neighbors in the same apartment building on 66th Street off Central Park West, the pair has been seeing each other in the elevator for decades.

For Conlon, the opportunity to conduct Figaro here comes soon after completing one of the longest runs of any festival director, an amazing 37 years (1979-2016) as music director of the Cincinnati May Festival, and a concurrent decade (2005-2015) directing the Ravinia Festival, which is the summer home of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Freed from these distinguished obligations, Conlon has been traveling and conducting in Europe, particularly in Italy, where he serves as the principal conductor of the RAINational Symphony Orchestra in Turin and on the radio all over the country.

Widely regarded as a conductor of singular authority when it comes to Mozart’s operas, Conlon, along with the specific choice of The Marriage of Figaro, comes to the Music Academy at the specific request of the current vocal fellows. In other words, for these brilliant young singers, the combination of Conlon and Mozart is a wish granted and a dream come true. When it comes to his personal feelings for this music, Conlon said, “Let me put it this way: I don’t think I could live without it.” Asked to put his enthusiasm for The Marriage of Figaro in context, the first point Conlon made was that despite offering an at-times scathing critique of aristocratic privilege, the opera is ultimately life-affirming for all the principal characters. Even Count Almaviva, who has abused virtually every woman in his large household, is forgiven in the magnificent extended finale.

Of course, that chorus of redemption necessarily resonates somewhat differently in a post-#MeToo era, and this dynamic perception is just the kind of thing that Conlon is quick to acknowledge and expand upon. He sees the story as driven by xand y axes of tension, with class conflict running along one and the battle of the sexes along the other. Sometimes these lines of force converge, while at others they contend with one another for supremacy. In the complex dance of disguise, misrepresentation, and mistaken identity that is Act 4 of Figaro, Conlon sees Figaro, a champion in the contest of wit with his master, Almaviva, as playing for the losing side in his role as a confused and jealous husband to Susanna.

Directed by James Darrah and presented in what is certain to be a gorgeous full production at the Granada, The Marriage of Figaropromises to be one of the great highlights of the season for Santa Barbara. As Conlon explained when I asked him what was most challenging about performing this particular work, “With Mozart, the artists onstage and in the orchestra alike are all completely exposed — everything shows, so everything has to be right.” Given that this summer’s cohort chose Conlon to lead their dream team, it’s going to be something to see.